This week, the Centre for Climate Justice concluded its mini-series on Palestine and Climate Justice with two powerful events. The series began with “Colonized Waters and Worldviews: Perspectives on Palestine” where Dr. Muna Dajani discussed the underlying colonial causes of violence and environmental injustice in Palestine.

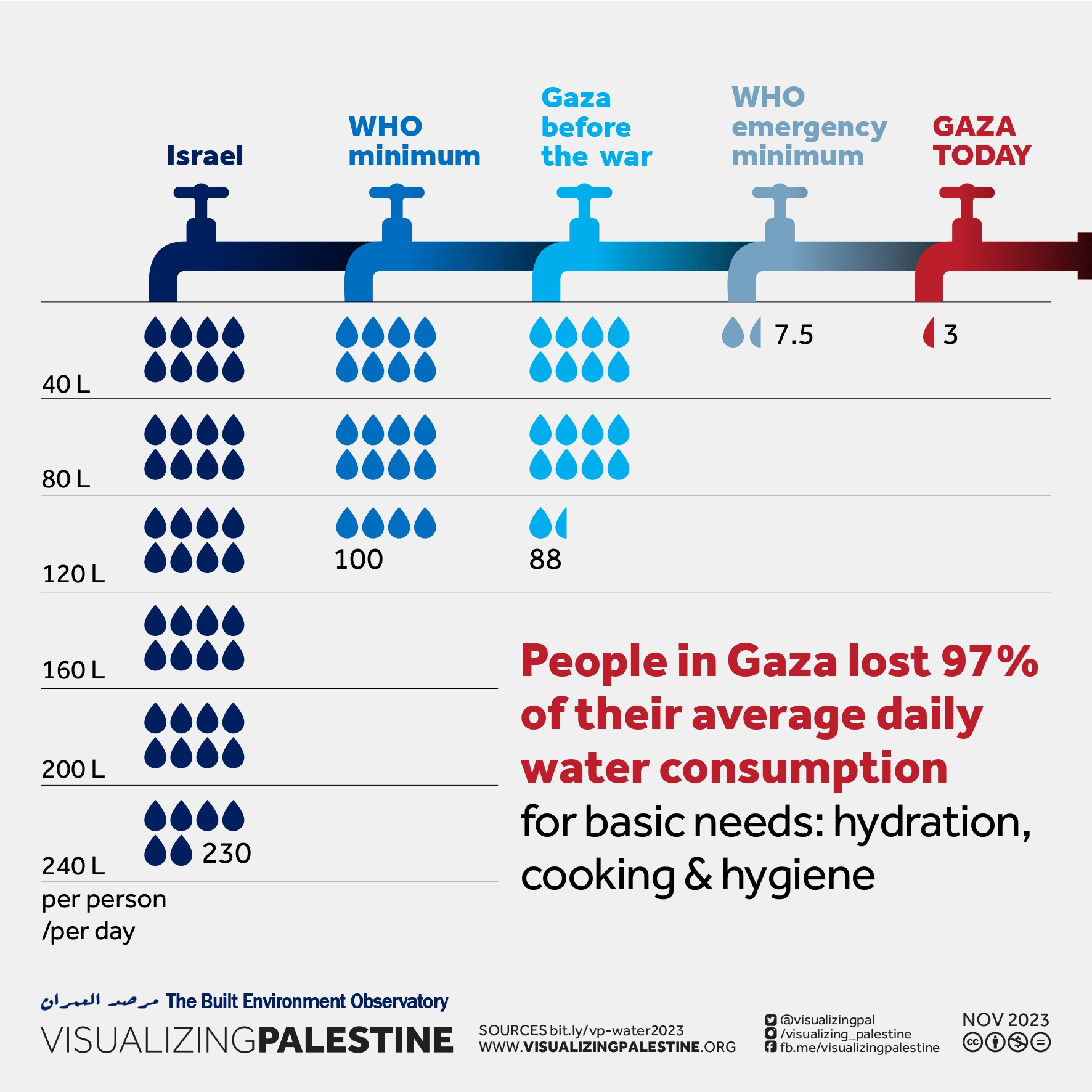

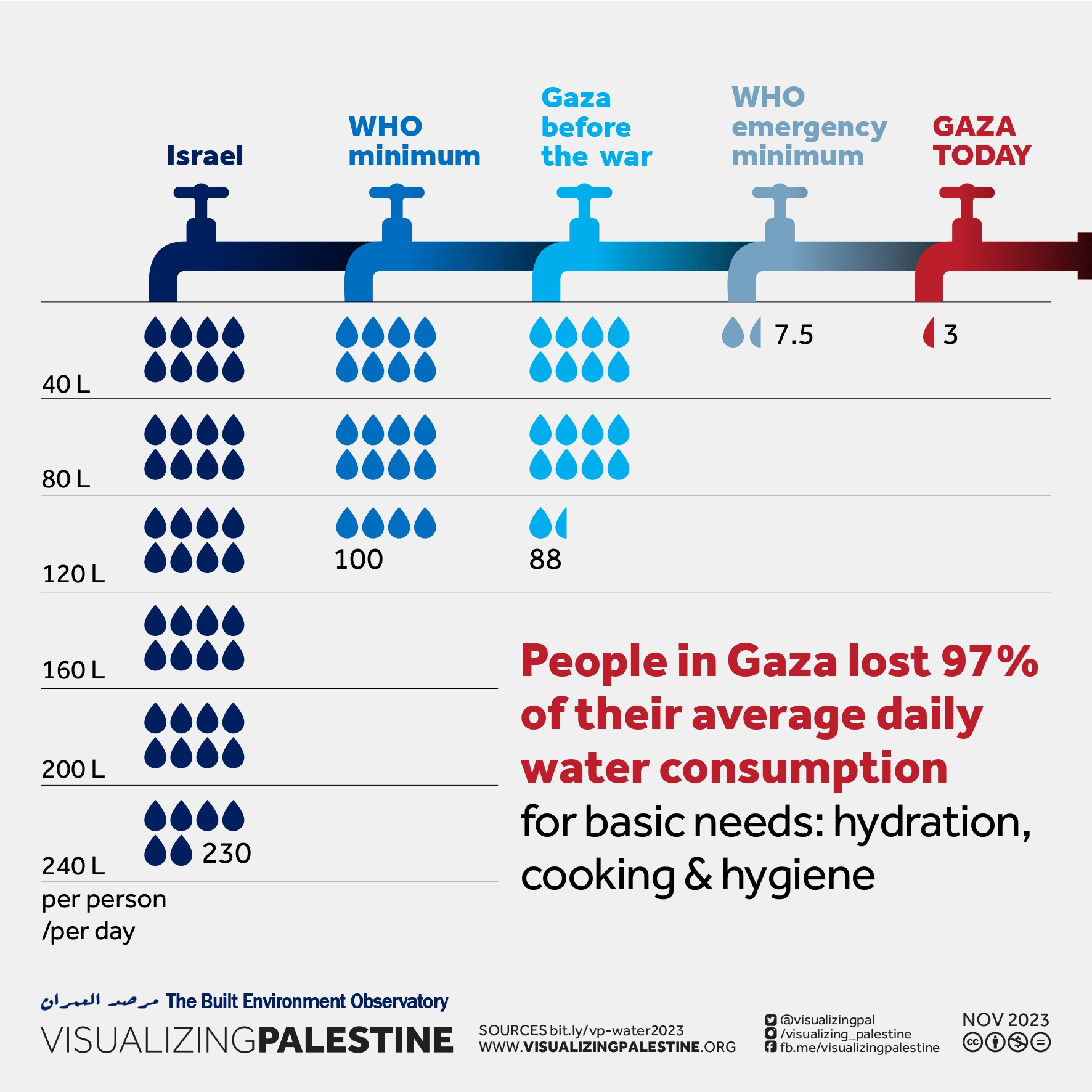

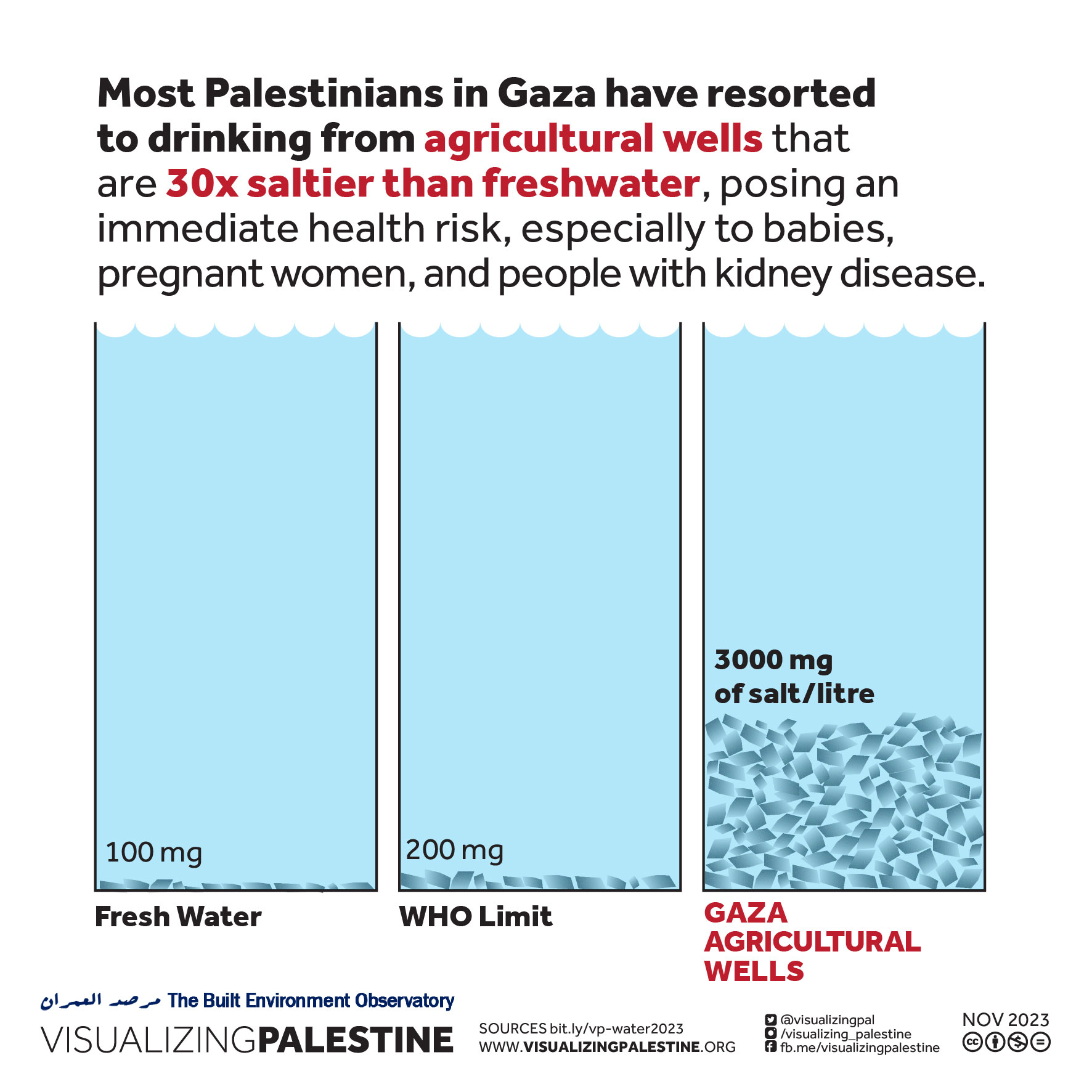

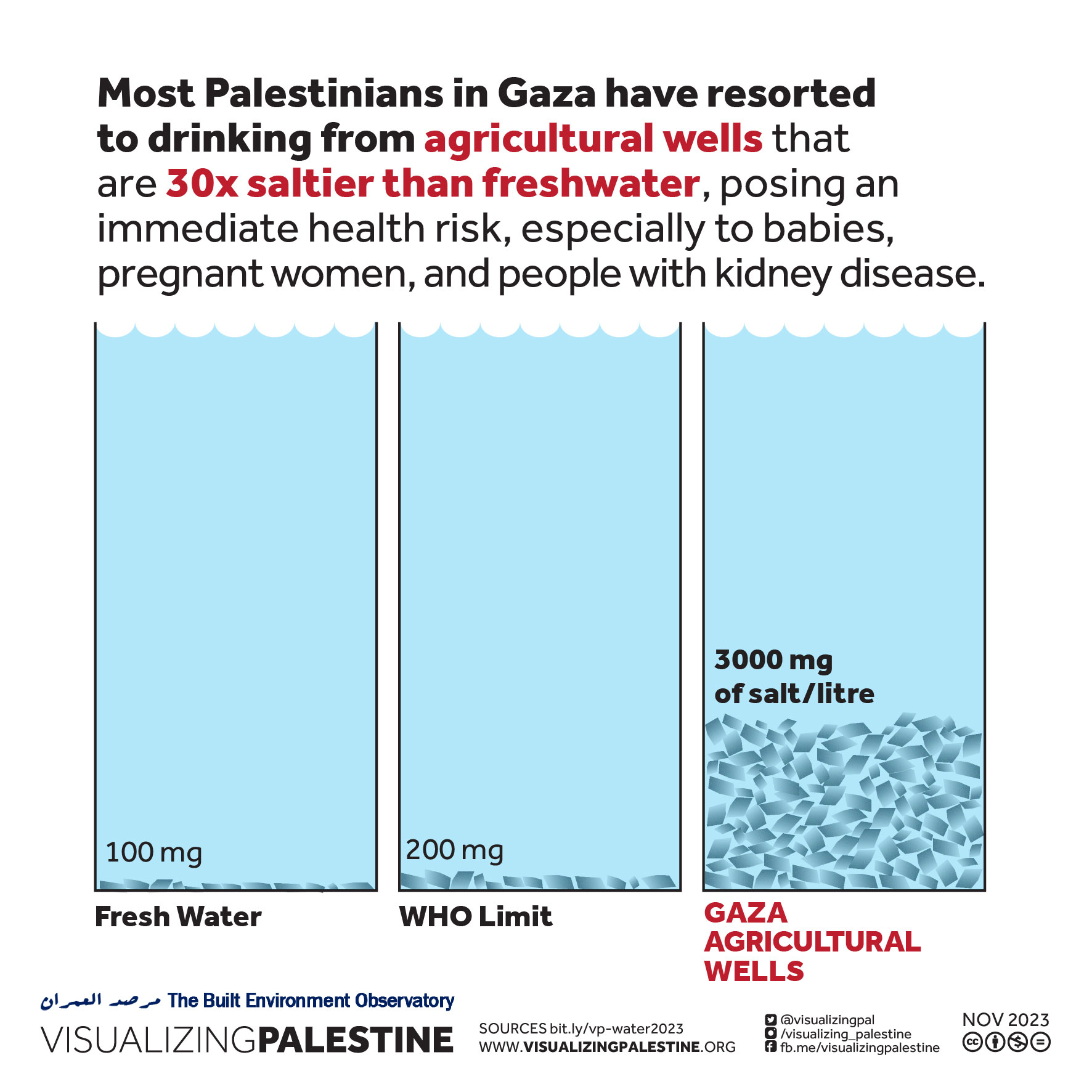

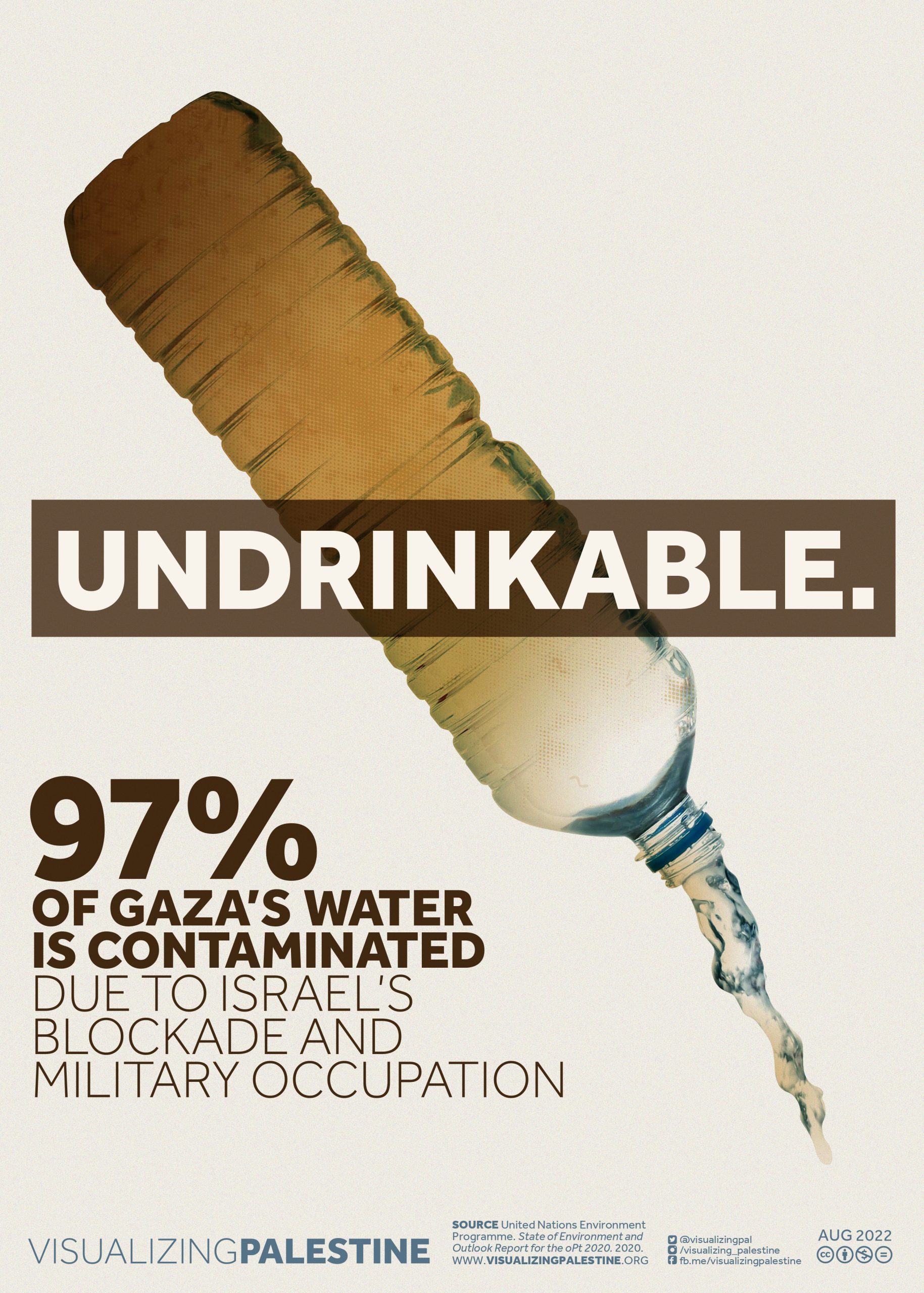

In her talk, Dr. Dajani explained “past is the present, and the present is the past. These are moments that continue to expose the structures of violence, the slow violence, and speaks of the multitudes of harm being inflicted on humans and the ecology replicated by systems of oppression that reveal themselves in moments like we are currently witnessing.” As for a collective way forward, Dr. Dajani shared that “solutions are needed, but we need solutions that are just and transformative, not apolitical fixes.” Dr. Dajani’s presentation was also accompanied by powerful data visualizations from the collective Visualizing Palestine, demonstrating Israel’s weaponization of water.

Credit: Visualizing Palestine

Credit: Visualizing Palestine

Credit: Visualizing Palestine

This event was a spectacular segway into the CCJ’s second and final event in its mini series where Executive Committee member Mohammed Rafi Arefin joined Batul Hassan and Patrick Bigger from the Climate and Community Project. Below we share Dr. Arefin’s introduction and framing for the event.

To access the event’s full recording and visual materials:

Palestine and Climate Justice: Military Emissions as Symptoms of a Genocidal Present and Future

Mohammed Rafi Arefin, PhD

I’d like to start with the acknowledgement that the Centre for Climate Justice is on the traditional, unceded, and ancestral land of the Musqueam people. At the Centre for Climate Justice we are working to ensure that this acknowledgement is taken seriously and the responsibilities it necessitates are at the heart of the Centre’s efforts engaging with First Nations and indigenous struggles near and far. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] Recent months have seen reactionary responses to Indigenous struggles for sovereignty from the reversal of policies that secured Indigenous rights in New Zealand and the unsuccessful constitutional referendum in Australia, to the recent pause of amendments to the Land Act here in British Columbia. In the face of rising reactionary and fascist responses to decolonization and liberation, the time is now for political education that connects the dots between seemingly localized struggles to build international connections and solidarity.

It is this kind of political education that Colombian President Gustavo Petro engaged in when at last year’s climate conference in Dubai, COP28, he stated, “what we see in Gaza is the rehearsal of the future.” This future was captured in a microcosm at last year’s COP. Before traveling to Dubai, the Israeli Environmental Protection Minister told the Jerusalem Post, “The climate crisis does not disappear even in these complex days when Israel is fighting on the battlefield… we must continue and act on the issue [of climate] here in Israel and globally. Israel’s participation in COP is crucial.”

This, I’d argue, is the future that Petro warns us of. A future where a state committing genocidal violence against a population and land it keeps under siege and occupation can position itself as a crucial actor in solving the complexity of climate change. How is this rhetorical feat achieved? The climate emergency must be depoliticized and presented as a technical problem, a problem that is disconnected from actors like settler colonial states fueled by extractive economies entrenching the structural drivers of the climate crisis, namely, colonialism, militarism, imperialism, and capitalism. On display at Israel’s pavilion was exactly this future—a presentation of four climate start-up companies from the regions around Gaza. A performance of technical climate solutions amidst a genocide.

The United States condemned the Colombian president’s statements not only because they dare to apply international law to Israel, but also because his comments synthesize struggles across geographies and across so-called issue siloes. Petro’s statements also synthesize across time, connecting a present-tense genocide with genocides of both the past and future. What does this rehearsal tell us?

At the Centre for Climate Justice, we are calling this fascism’s “long arc,” and it carries several important lessons. Among them: Climate justice requires sovereignty over lands, but also the sovereign production of knowledge to tend and care for the land. Israel has destroyed or rendered inoperable every single one of the universities in Gaza including: Islamic University of Gaza, Al-Azhar University, Al-Quds Open University, University College of Applied Sciences, University of Palestine, Israa University, University of Gaza, Al-Aqsa University, Palestine Technical College, Palestine College of Nursing, and Arab College of Applied Sciences. Israeli attacks have killed hundreds of educators and academics and injured hundreds more. Palestinian scholar Karma Nabulsi called this kind of destruction scholasticide: the systematic destruction of a population’s pedagogical systems and educators. In Towers of Ivory and Steel, Maya Wind demonstrates how Israeli institutions of higher education have not only been silent about such destruction, but have long been complicit and active forces in Palestinian repression. What institutions will train the many Gazan engineers, social scientists, soil scientists, hydrologists among others needed not for the reconstruction of the status quo but for an environmentally just, liberated Palestine? Scholasticide is a climate justice issue.

Calls for climate justice are about intervening in everyday lives to remake our economies and societies and much of this work is done through infrastructure. The destruction of Gaza’s universities is part of a larger tactic, urbicide. Urbicide is the targeting and destruction of basic urban infrastructures (housing, electricity, sewage plants, water treatment facilities) with the aim of debilitating city life in the present and into the future. Geographer Stephen Graham has argued that this kind of warfare, which targets the underlying structures of city life is the hallmark of contemporary warfare from the 2003 Iraq war to what we are seeing in Gaza today. How can we re-envision infrastructure for just a future when Gaza’s built environment is being reduced to a toxic rubble poisoning generations to come? Urbicide is a climate justice issue.

While the scenes of urban destruction fill our TV screens and our social media feeds, the destruction of Gaza’s non-urban lands and livelihoods fall out of immediate view. The Guardian reported that satellite imagery shows that Israel has destroyed about 38-48% of Gaza’s tree cover and farmland. Ecocide, perhaps it goes without saying, is a climate justice issue.

And yet our governments and state institutions here in North America consistently refuse to name these patterns as crimes against humanity, and wages a multipronged information war against those of us who feel a moral duty to describe and denounce them. And so it must be that Petro is right: What we are seeing in Gaza is a rehearsal of the future. A future where scholasticide, urbicide, and ecocide are not incidental, but perhaps necessary to any apolitical solution to the climate crisis that severs it from its root drivers and institutions– institutions like genocidal militaries bent on solving political questions of popular liberation with state violence. To again quote Gustavo Petro, “Gaza is just the first experiment in considering us all disposable.”

But Gaza is also teaching us how to resist and reconfigure this rehearsal. In a recent visit to UBC, Palestinian scholar Sherine Seikaly responded to my question about the role of the climate movement in resisting genocide. She replied mass movements from climate to labour are already doing so, and we can see this in the outpouring of people into the streets of cities around the world, week after week to support Palestine. Why do people keep showing up? Dr,. Seikaly argued it is because people around the world are seeing in the struggle of Palestinians glimpses of their own struggles, captured by the question “How can we hold ground, while the earth beneath our feet is disappearing?” That is a question for Palestine and Palestinians, but also for everyone living where seas are rising, where glaciers are disappearing, and rivers are drying.

One answer to this question “How can we hold ground?” is through political education that illuminates the contours of shared struggles. I’m happy to be here with Batul Hassan and Patrick Bigger. Batul is policy manager at the Climate and Community Project where Patrick serves as the Research Director. Batul and Patrick have been involved in path breaking research on the climate costs of militarism and centering Palestine in struggles over climate justice. For the rest of our time together, Batul and Patrick will present from CCP’s report, “Ceasefire Now, Ceasefire Forever: No climate justice without Palestinian freedom and self-determination” and related research on military emissions.

Batul Hassan and Patrick Bigger’s presentations and discussion offered fervent arguments for how we ought to view the ongoing genocide in Palestine, best framed by Bigger’s remarks that “to confront the drivers of the climate breakdown are also to confront the drivers of apartheid, militarism, and perpetual war. An immediate, permanent ceasefire in Palestine, and an end to all occupation and apartheid, is the only viable path toward lasting peace, security, and survival in the climate crisis.”

Hassan and Bigger explored the connections of this violence with both underlying colonial forces at play and the military industrial complex. The effects of colonialism, they argued, are no better demonstrated than by the fact that global popularity for Palestinian liberation and self-determination has not resulted in an immediate and permanent ceasefire. Hassan shares that “even though we’re the majority, we still haven’t yet built, as the left, the level of organization that we need to actually challenge the power and scale of the US imperial infrastructure. […] Our theory of change is that we can’t just sit within our existing coalitions. We need to be broadening outside, we need to be bringing people in, if we want to win at the scale that’s needed — whether that’s climate action, a free Palestine, or a decarbonized system, we need many many more people on our side and in power to make this happen.”

As for the enormous influence of the military industrial complex, Hassan and Bigger argued that it is “not just something that happens abroad, [but] it’s something that seeps into every one of our systems here” in the United States and Canada through over-policing, our incarceration systems, the militarization of our borders, and more. Hassan said that the military industrial complex “is an industry that needs to be considered with the same amount of seriousness as we consider the oil and gas industry. If we don’t do that, then we are missing a huge part of the fight and that’s not setting ourselves up to win.”

The largest takeaway of the event, and of the CCJ’s mini series as a whole, is amazingly summarized by the Climate and Community Project and Patrick Bigger’s assertion that “apartheid is incompatible with climate justice, but inevitable without it.”

There is much more to say about how the climate justice movement needs to relate to this fight against genocides, as well as to decarbonize and transform our societies, economies, and the military industrial complex. It is clear from this discussion that we need to build power while keeping in mind the wholesale and sweeping change needed in our communities locally and intentionally. For more on these topics, be sure to check out the full recording!

About the series’ speakers:

Dr. Muna Dajani is a Fellow in Environment at the Geography and Environment Department at LSE, and she is an action researcher with a background in critical political ecology. Her work aims to understand environmental and water governance through decolonial and critical lenses. She holds a PhD from the Department of Geography and Environment at the London School of Economics (LSE).

Batul Hassan (she/her) is the policy manager at Climate and Community Project, where she focuses on health, care, and education research that supports transformative climate policy that benefits the multiracial working class. She has a background in public health, migration, and labor organizing.

Dr. Patrick Bigger is the Research Director at the Climate and Community Project. His eclectic scholarly and policy research contends with a range of environmental and political challenges, from the US Military’s role in the climate crisis to the failures of market mechanisms to slow biodiversity loss. His work at the intersection of militarism and the climate crisis won the 2018 Virginie Mamadouh Outstanding Research in Political Geography Award.

Mohammed Rafi Arefin is an Executive Committee member of the Centre for Climate Justice and Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of British Columbia. Drawing on urban political ecology and environmental justice, science and technology studies, and discard studies, his research and teaching are focused on urban environmental politics with a specific focus on waste and sanitation.